This week, my client Ty Hargrove was sentenced to die in prison.

In 2017, Ty killed his estranged girlfriend, Shaekeya Gay, in front of a Henderson Food Lion. He was 23 years old. The crime was caught on video, and Ty never denied his guilt.

The district attorney announced he was seeking the death penalty. But almost immediately, he made Ty an offer: If Ty would plead guilty to first-degree murder, the death penalty would be dropped. Under North Carolina law, there are only two possible punishments for first-degree murder, death by execution or life in prison without parole — in other words, death by incarceration. If Ty took this plea bargain, he would never be executed, but he would die in prison.

These types of plea offers are common in North Carolina death penalty cases, and it’s a terrible choice for a young person. Both the death penalty and life without parole are intended to dehumanize, to send the message that if someone does something so terrible, their life has no value. That’s the law, but it isn’t the truth. The truth is that all lives have value. All of us have caused harm, and we’ve all been harmed, too. We are so much more than the worst thing we have ever done.

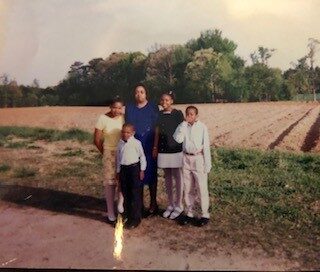

Ty certainly is. He is a soft-spoken young man who is treasured by his family and friends and is especially close to his small nieces. Until this crime, he had no criminal record. Born in extreme poverty in rural Vance County, Ty watched his beloved father die of cancer the day before his eighth birthday. He dropped out after middle school because his underfunded school district failed to provide him with meaningful special education services to address his learning disability. Plagued by chronic depression, Ty self-medicated with drugs because he couldn’t afford mental health treatment. When his drug use destroyed his relationship with his first real love, he didn’t know how to deal with his heartbreak and ended up killing the person who meant the most to him. At the time of the crime, Ty’s brain wasn’t even fully developed.

Ty chose not to sign his life away, and we started selecting a jury in mid-August. With Ty sitting just a few yards from them, the judge and prosecutors asked jurors to affirm they were capable of voting to execute him. Several weeks into this grueling and traumatic process, Ty made the choice to accept the plea bargain. I am relieved he won’t get a death sentence. But life without parole is not justice. Ty is capable of change and growth and deserves a chance to do better, despite the terrible harm he has caused.

Ty is not the only young man of color who has been thrown away by our criminal punishment system. According to Ben Finholt, director of the Just Sentencing Project at Duke Law School, there are currently 1,556 people serving life without parole sentences for murder in North Carolina. Of those, a stunning 72% (1,117) had no prior criminal record, and 43% (664) were under 25 at the time they committed their crime. 69% (1,075) are, like Ty, people of color.

Life without parole is a creation of our modern carceral state and has only been part of North Carolina law since 1994. There is growing national recognition that life without parole is a failed experiment. The American Bar Association recently called for its abolition. Men serving life without parole in Louisiana have contributed their first-person accounts to a project called The Visiting Room. Their stories show how people can change, even after they’ve been thrown away.

The death penalty should not be used as a tool to force people to sign their lives away. It shouldn’t exist at all. And neither should life without parole.