On April 13, 2023, the NC Commission on Racial and Ethnic Disparities in the Criminal Justice System (NCCRED) will hold a symposium at Shaw University in Raleigh titled Undue Harm: Undoing the Legacy of Confederate Monuments. The event will highlight the harms Confederate monuments inflict from multiple perspectives in order to underscore not only the urgency of eradicating these symbols of white supremacy, but also the need to address the immense harm they have inflicted. To register, click here.

NCCADP is a co-sponsor of the symposium, has participated in the planning of Undue Harm, and strongly supports NCCRED’s Campaign to Remove Confederate Monuments. NCCADP agrees that monuments to white supremacy are not merely historical artifacts; rather, they continue to inflict immense harm today. Here, CDPL attorney Aiesha Krause-Lee details the harm inflicted on both her client and herself when a trial was held in a North Carolina courthouse displaying white supremacist iconography.

Last summer, I participated in a capital trial in Vance County for Ty Hargrove, a Black man who had lived in Vance his whole life. As a young Black lawyer with family roots only an hour away from Vance, I was excited to return to the South to practice law after graduating from law school in 2021. But I was also apprehensive about the culture and prejudices I expected to face practicing in more rural counties like this one. In this case, I was the only Black attorney. The judge, prosecutor, and other defense attorneys were all white.

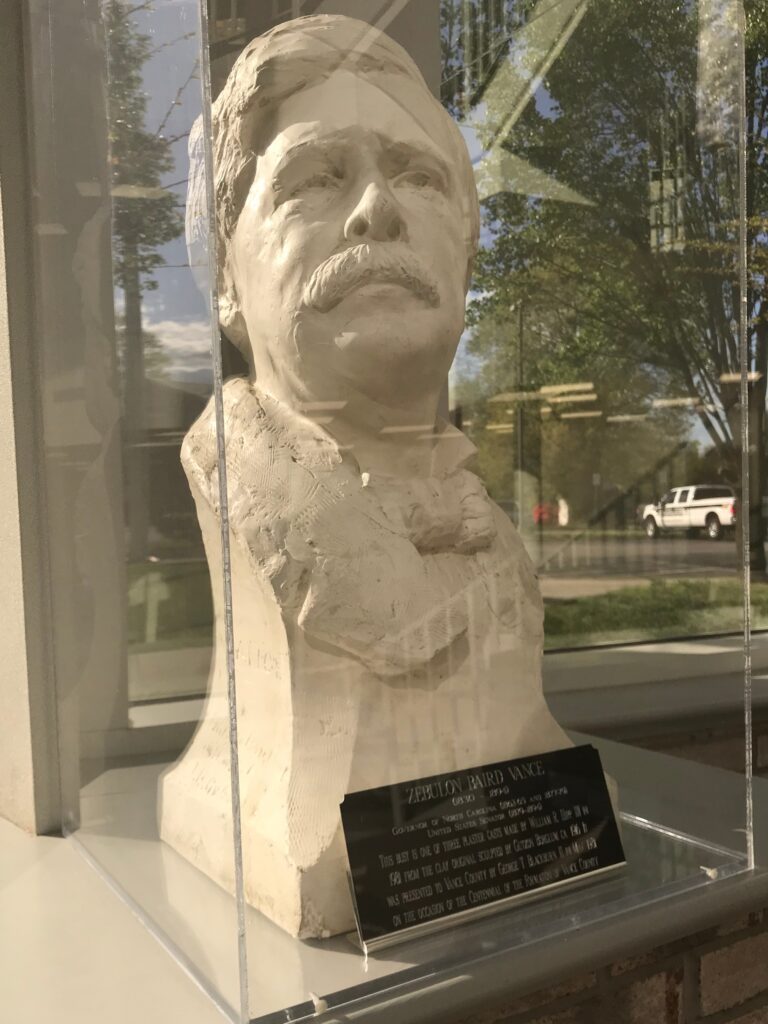

My first time in the courthouse, I noticed the lobby featured a giant portrait and accompanying bust of former North Carolina Governor Zebulon Vance, the county’s namesake. I knew that Vance was a Confederate soldier, staunch defender of slavery, and an avowed racist who argued strongly against emancipation.

As a capital defense attorney, I am acutely aware of how the death penalty disproportionately affects Black men and is a part of the legacy of racism and white supremacy that people like Zebulon Vance stood for. The sight of Vance’s image in a courthouse where my client’s fate would be determined was deeply troubling.

Our defense team filed a motion to remove the portrait and bust for the duration of Ty’s trial, arguing these monuments honored the ideology of white supremacy. We felt that the portrait’s display evinces bias against African Americans that could have an effect on potential jurors as well as our client, jeopardizing his right to a fair trial.

The judge declined to order the temporary removal of the images, citing uncertainty as to whether jurors would even notice the portrait.

But I noticed it. It was the focal point in an open atrium, visible from all three floors of the courthouse. Every day when I walked up the stairs to the courtroom on the second floor, I felt Vance’s eyes following me, a daily reminder that the legal profession wasn’t intended for me or people who look like me. The fact of the portrait was offensive to me, but almost worse was the judge and prosecutor’s belief that its display didn’t have a tangible effect on people, white and Black, entering the courthouse.

In the context of a death penalty trial, the harm of Confederate imagery is even more pronounced. The death penalty is already disproportionately applied to Black defendants, and the presence of such imagery reinforces the perception that the system is rigged against us. It makes it even more difficult for Black lawyers to represent their clients effectively and for Black defendants to receive a fair trial. The message these monuments send is clear: The courthouse is a place where white supremacy is tolerated and honored.

We cannot move forward as a society until we confront our past and acknowledge the harm that has been done. That means removing Confederate monuments and other racist imagery from our courthouses and other public spaces. It also means acknowledging the role that white supremacy has played in shaping our legal system and committing to creating a more just and equitable future for all.