Henry McCollum lived in New Jersey but had come to rural North Carolina to spend time with his mother and his brother, Leon Brown. It was the autumn of 1983. Henry was 19, and Leon was just 15. Henry had been in Robeson County for a few weeks when the body of 11-year-old Sabrina Buie was discovered in a soybean field just a short distance away from his mother’s home. The little girl been raped, and suffocated. Police in the tiny town of Red Springs began interviewing local residents, searching for suspects.

One police officer came across a high school student who repeated a rumor she’d heard at school: Henry McCollum, a teen from out of town, seemed suspicious and might have been involved in the crime. Henry had intellectual disabilities, which may have been why other teens felt he behaved strangely. When officers showed up at his mother’s house, Henry went to the police station voluntarily. It was evening, and a group of law enforcement officers kept him in an interrogation room until late in the night, demanding that Henry tell them about the crime, promising him that if he gave them the facts about the crime, he would be allowed to go home. After four and a half hours of questioning, Henry broke. He told the officers a story filled with details they’d given him, about a rape and murder he had nothing to do with. The officers wrote up a grisly confession and Henry, who could barely comprehend the written document, signed it. And then he asked, “Can I go home now?” He had no idea that he wouldn’t go home again for more than three decades.

The officers wrote up a grisly confession and Henry, who could barely comprehend the written document, signed it. And then he asked, “Can I go home now?” He had no idea that we wouldn’t go home again for more than three decades.

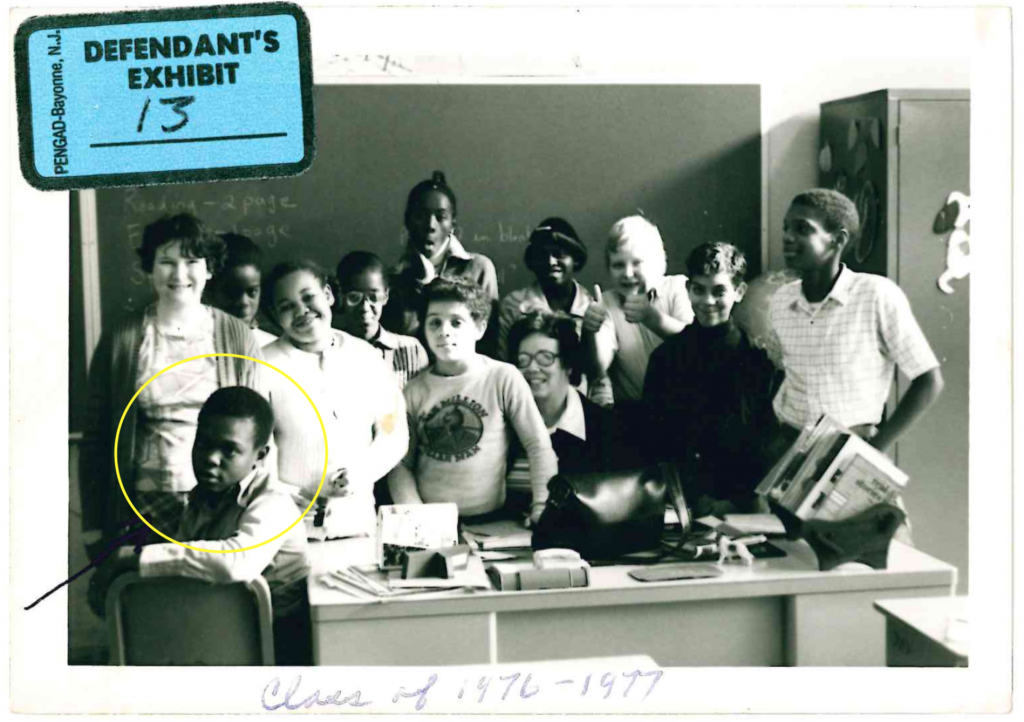

As Henry invented the details of the rape, he added other characters to the scene to share responsibility for the awful crime. He said that his brother Leon had been with him, along with two friends. By coincidence, Leon and his mother were already at the police station; they’d come to wait for Henry. Police pulled Leon into another interrogation room, and extracted a confession from him too. Leon, who was more profoundly disabled than Henry, could not even read the document he signed just a half hour after Henry’s confession. It conflicted in significant ways with Henry’s account, and both confessions pointed to two other boys who police later determined could not possibly have been present. Yet, those two confessions — coerced, conflicting, and patently false — became the evidence that prosecutors would use to send two innocent, poor, black, disabled teenagers to death row.

Henry and Leon quickly retracted their confessions, but it was too late. In 1984, a jury sentenced both of them to death. In 1991, they won a new trial, and Leon was resentenced to life in prison. However, Henry was again sentenced to death. His confession was, once again, the key piece of evidence. During his years on death row, Henry’s case became notorious. U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia pointed to the brutality of Henry’s crime as a reason to support capital punishment. During North Carolina legislative elections in 2010, Henry’s face showed up on political flyers as an example of a brutal rapist and child killer who deserved to be executed. Henry continued to proclaim his innocence to anyone who would listen.

Finally, Leon wrote to the N.C. Innocence Commission, a state agency that agreed to investigate the case. What they uncovered was shocking. Investigators knew at the time that fingerprints found at the scene didn’t match Henry or Leon, but they never compared the fingerprints to other possible suspects. And just a few weeks after Sabrina Buie’s killing, another young woman was raped and murdered in Red Springs. Joann Brockman, 18, had also been raped, asphyxiated, and left in a field. The culprit was a man named Roscoe Artis, who had a long record of serious assaults against women. Artis lived next to the field where Sabrina’s body was found, yet he had never been investigated as a suspect in her death. The Innocence Commission staff unearthed items that had been left by Sabrina’s body — clothing, beer cans, cigarette butts — and conducted modern DNA testing. They found no DNA belonging to Henry and Leon, but on one cigarette butt, they found a perfect match with Roscoe Artis.

Based on the Commission’s overwhelming evidence of innocence, the brothers were released from prison in 2014. In 2015, then-Gov. Pat McCrory granted the brothers a full pardon of innocence. Also that year, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer cited their case as a reason to outlaw the death penalty.

Today, Henry is rebuilding his life with the help of family. Leon, whose severe disabilities were compounded by the trauma of prison, is living in an institution. Both are pursuing a civil lawsuit against the agencies that wrongly imprisoned them. Roscoe Artis remains in prison, serving a life sentence for Brockman’s murder. He has not been prosecuted for Sabrina’s murder.

Learn more:

Read the Center for Death Penalty Litigation’s in-depth story of Henry and Leon’s dramatic exoneration, read their report Saved From the Executioner

Watch this fascinating one-hour documentary about the case from Death Row Stories (Episode 8)

Read the Marshall Project’s story about what happened to the brothers after their exoneration, The Price of Innocence

Read more stories of innocent people sent to NC death row