In 1998, a jury was called to decide the fate of brothers Tilmon and Kevin Golphin, black teenagers who were accused of killing two white law enforcement officers during a traffic stop. Tilmon was 19 and Kevin was just 17 when the crime occurred, yet under the law at the time, both faced the death penalty.

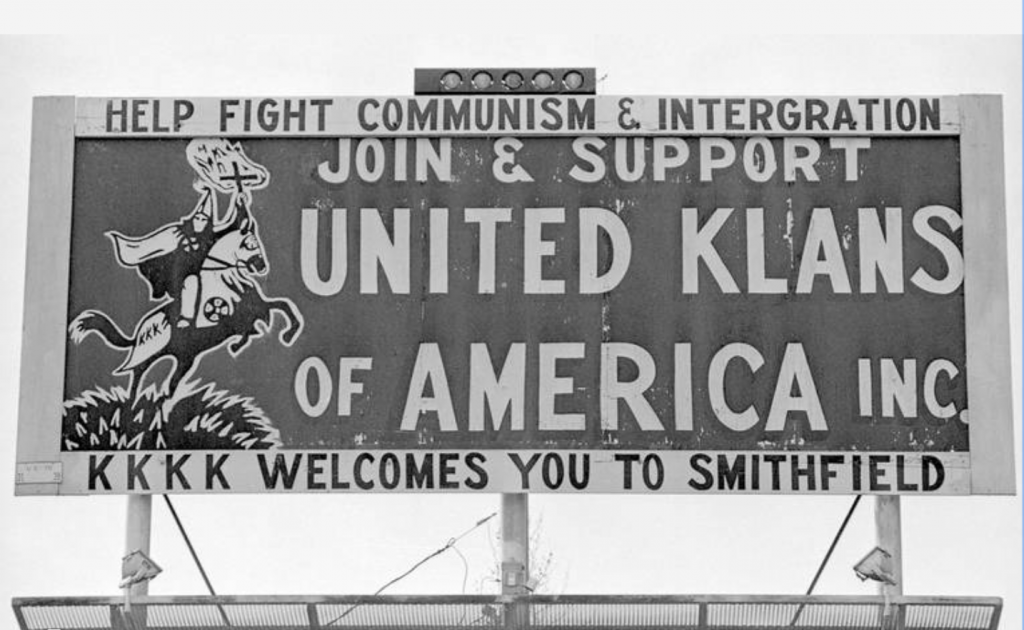

The shooting happened in Fayetteville, but because of a media frenzy, the trial had to be moved. The judge chose Johnston County, a heavily white, conservative county that for many years welcomed visitors with a sign advertising it as the home of the Ku Klux Klan.

During jury selection, a black member of the jury pool overheard two white members agreeing that the brothers “never should have made it out of the woods” where police arrested them. The black juror reported this baldly racist comment to the court. Yet, the judge made no attempt to identify or remove the white jurors.

Instead, the prosecutor aggressively questioned the black man about why he reported the incident, then struck the black man from the jury, citing his report as one of the reasons.

The same prosecutor questioned potential black jurors about whether they listened to Bob Marley or were familiar with Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie, implying that they might sympathize with black defendants who practice Rastafarianism. No white jurors were asked similar questions.

In the end, the prosecutor struck all but two of the black jurors. The defense attorneys had to strike another who they felt wouldn’t be fair to their client. That left a jury of eleven whites and one black woman to decide the fate of two black teens. The white jurors who made racist comments were never identified, so it’s possible they were members of the final jury.

In front of this skewed jury, the prosecutor depicted Rastafarianism as a white-hating cult, rather than a religion that preaches black empowerment and redemption. The Golphin brothers were badly abused children growing up in a culture of violence, addiction, deprivation, and racism, factors that could have led the jury to choose life sentences. But the boys’ tragic life story sparked no mercy in a jury with such limited understanding of their backgrounds.

Both were sentenced to death. Kevin later received a life without parole sentence after the law was changed to prohibit death sentences for children.

In 2012, Tilmon was temporarily removed from death row and sentenced to life without parole after his attorneys proved, under the Racial Justice Act, that prosecutors used racist jury selection practices. It’s illegal to strike jurors because of their race, but a judge found that’s exactly what happened at Tilmon’s trial.

However, Tilmon was soon sent back to death row when his Racial Justice Act case was overturned on a technicality. In 2020, the N.C. Supreme Court once again ruled that he could not be executed because of the clear evidence of racism in his case. He is now serving life without parole.

Watch Tilmon’s longtime attorney Ken Rose and poet Cameron L. Bynum speak about the case at the Carolina Justice Policy Center’s Poetic Justice event in 2018.