Each November, America honors those who served in the armed forces. We speak of courage and sacrifice, of the price of freedom and the duty of remembrance. But in North Carolina, many of those same veterans sit on death row, waiting for the state to decide when they will die.

Veterans and the Death Penalty in America

Across the country, veterans bear an unequal burden in the capital punishment system, making up at least 10 percent of all people on death row in the US.

Of the 41 people executed in the United States so far this year, 6 were military veterans. Five of those men were killed by Florida, a state that will soon execute another veteran, Bryan Jennings.

To honor veterans, we must confront the ugly contradiction at the heart of American justice. We send people into war, train them to endure violence and fear, then routinely abandon them when those experiences follow them home.

Veterans on Death Row in North Carolina

North Carolina’s death row population reflects that dissonance. Although veterans only make up about 8 percent of North Carolina’s adult population, nearly 20 percent of the people on the state’s death row served in the military. Of the 122 people who have been condemned to die, 23 are veterans.

Veterans currently on death row have served in nearly every branch of the military, including the Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps, Army Reserves, and National Guard. Five saw active combat. One came home bearing shrapnel wounds. Among those whose records are known, the average length of service was more than 5 years.

This is the naked cost of neglect. Many veterans return from war with invisible wounds that the state fails to address, and when these wounds go untreated, they can lead to devastating crises.

Mental Health, Military Service, and the Cost of Neglect

According to the North Carolina Institute of Medicine, nearly 30 percent of the state’s veterans live with disabilities, over 7 percent live below the poverty line, and many struggle with post-traumatic stress, traumatic brain injuries, and substance use disorders. These intersecting risk factors increase the likelihood of involvement with the criminal legal system. Studies show that approximately 33 percent of veterans have a history of arrest, compared to 20 percent of the nonveteran population.

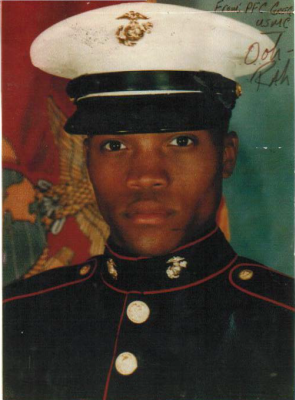

Warren Gregory served in the Marine Corps during the first Gulf War, where his unit endured oil fires, missile attacks, and constant bombardment. He returned home decorated with six honors, including a Combat Action Ribbon and a Good Conduct Medal, but he received no screening for trauma and no help processing what he had seen. Haunted by nightmares, he began drinking and using drugs to quiet his thoughts. His untreated post-traumatic stress disorder spiraled into a crisis that ultimately ended in violence. Today, he lives on death row in Raleigh’s Central Prison, waiting for the state to put him to death.

James Floyd Davis, a Vietnam veteran, came home with shrapnel wounds and hearing loss from combat. During his two tours, he saw nearly constant combat, leaving him with severe PTSD and psychosis. When he committed a workplace murder decades later, the jury that sentenced him to death heard almost nothing about his service or his mental illness. In 2009, while living on death row, Davis finally received a Purple Heart to honor the sacrifices he made on behalf of his country.

These stories are the predictable result of a system that recognizes valor in war but not vulnerability in peace. The trauma of combat reshapes lives, but the legal system often refuses to see it. Veterans’ military training is often portrayed in court as evidence of danger, while their service and resulting mental health struggles are minimized or ignored.

What True Honor Requires

If Veterans Day is meant to honor sacrifice, it must also challenge us to confront how we treat those who served once they come home. We cannot claim to value veterans while executing them. To truly honor those who have sacrificed their mental health for their country, we must invest in health care, ensure access to treatment and housing, and create a criminal legal system that seeks to understand and heal trauma instead of punishing it.

When we execute veterans, we do not uphold justice. We deepen the wounds of war and show just how far we are from the ideals we claim to celebrate.