Three-quarters of the 136 people living on North Carolina’s death row were sentenced to death in the 1990s. But our large death row is just one of the remnants of that decade’s racist, tough-on-crime rhetoric. We also have dozens of people in prison who were sentenced as teenagers to life without parole or other draconian sentences that leave them virtually no hope of release.

However, in June, the North Carolina Supreme Court took a step toward excising that legacy, when it ruled that children convicted of crimes should at least get a chance at regaining their freedom before they reach old age. In two rulings, State v. Kelliher and State v. Connor, the court declared that people convicted of crimes committed as children should serve no more than 40 years before becoming eligible for parole.

This decision is barely a fraction of what’s needed to address our system’s excessive sentencing. In reality, only a handful of those eligible for parole are actually granted it, meaning that many people will still spend their entire lives behind bars for crimes committed as children.

However, it was refreshing to read these decisions and see the court repudiate one of the most devastating racist tropes of the 1990s: the myth of the “superpredator.”

Back then, criminologists and pundits warned of a coming wave of “radically impulsive, brutally remorseless” children, “elementary school youngsters who pack guns instead of lunches” and “have absolutely no respect for human life.” These children were, not surprisingly, presumed to be Black.

Based on this junk science, North Carolina passed harsh laws targeting children. Until 2012, any child convicted of first-degree murder was automatically sentenced to life without parole. North Carolina ranks among the top ten states in the country for sentencing children to life without parole and, according to a Duke University report, more than 90 percent of teens who received this draconian sentence are children of color.

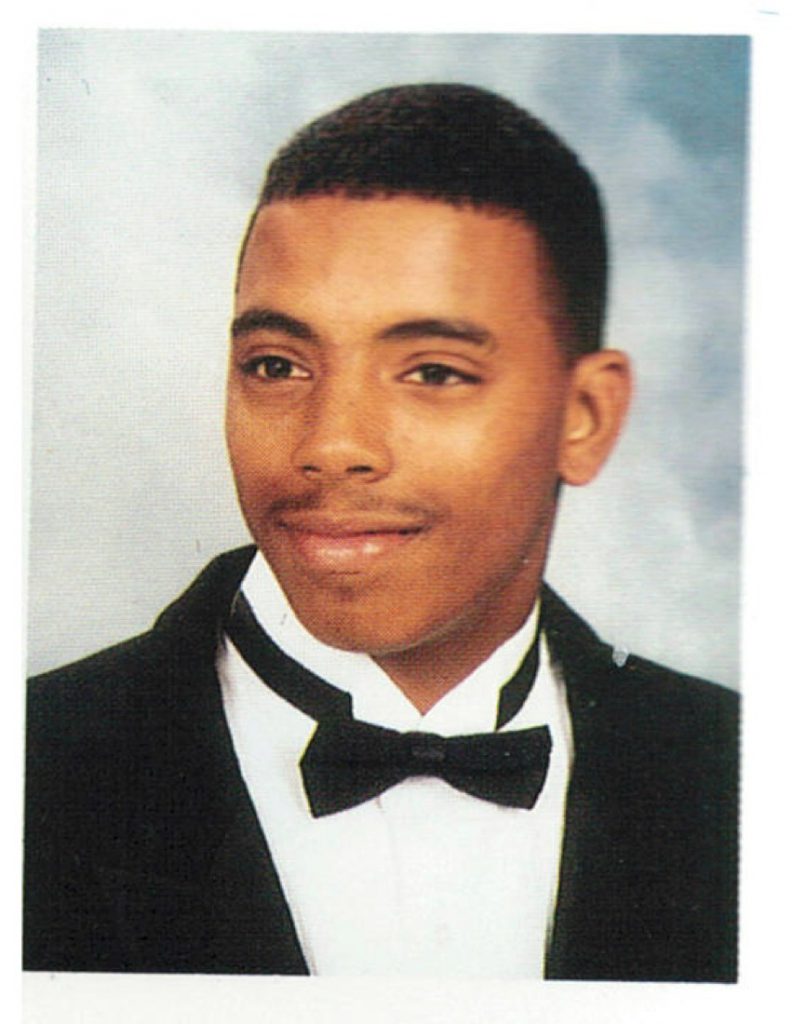

The superpredator myth fed the death penalty too. In 2001, two Black teenagers were sentenced to death in Onslow County after the prosecutor argued to the jury that these adolescents were akin to “the predators of the African plain.” Twenty people are on death row for crimes committed before they turned 21; a dozen of them were still teenagers.

In Kelliher, the state’s highest court acknowledged that the predictions of a wave of child crime never came to pass and that state legislative actions in the 1990s were taken during “an environment of hysteria featuring highly publicized heinous crimes committed by juvenile offenders” and that recent scientific evidence and empirical data “invalidated the juvenile superpredator myth.”

The court wrote, “We now recognize that our practice of describing children as ‘predators’ fundamentally misapprehended the nature of childhood and, frequently, reflected racialized notions of some children’s supposed inherent proclivity to commit crimes.”

We’re grateful the court recognized no child’s life should be thrown away, and society’s ideas about public safety are often shaped by prejudice and hysteria rather than facts. Now, we hope they will take on the death penalty, another policy shaped by racist hysteria and the idea that some people are disposable.

The reasons the court gave for abolishing life without parole for children are also reasons the death penalty should be found unconstitutional. For instance, the court noted that life in prison is extreme because juvenile offenders disproportionately experience childhood trauma. Most of the men and women living on North Carolina’s death row were also victims of childhood abuse and trauma. The court also pointed out that, under the North Carolina constitution, the purpose of prison is rehabilitation. Rehabilitation doesn’t include killing.

The death penalty is the pinnacle of our criminal punishment system’s failures, and the North Carolina Supreme Court has the power to end it.