The U.S. Supreme Court says the death penalty is intended for the most culpable defendants who commit the most heinous crimes. In practice, it often falls on people with intellectual disabilities and severe mental illness — those with a diminished capacity to understand their actions or to participate in their defense.

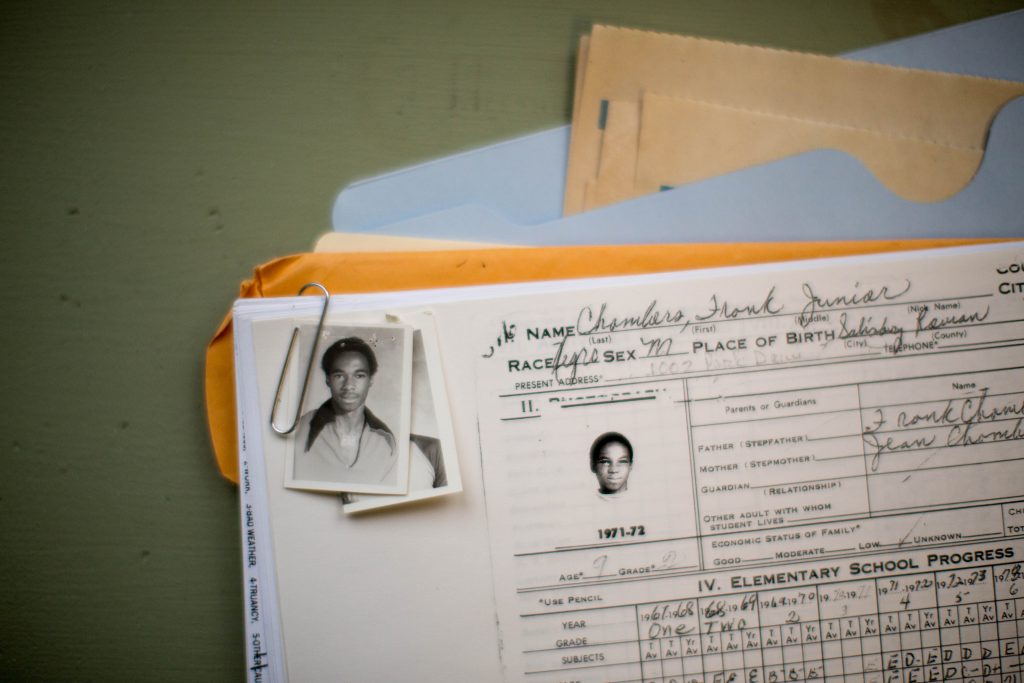

Under a 2001 North Carolina law, the death penalty is prohibited for people with intellectual disabilities. However, this protection is unevenly applied, because the state often fights to execute people by pointing to a specific IQ score that is slightly above the state’s cutoff — attempting to apply a “bright line” standard when a range of IQ scores and information about daily function are far more accurate in determining intellectual disability. This practice means that many people with clear disabilities still face execution in North Carolina.

There are even fewer protections for those with mental illness. There is no law preventing people with even the most severe mental illness from being tried capitally. Some people sentenced to death in North Carolina have schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders that cause delusions and hallucinations. Some have severe post-traumatic stress disorder, either because they are war veterans or suffered horrific childhood trauma. They did not have fair trials because their illness made it impossible for them to cooperate with their lawyers or make rational decisions.

A death penalty that preys on the most vulnerable people in our society makes a mockery of justice.

Right now in North Carolina:

- Intellectual disabilities and mental illness make people more susceptible to police pressure to confess, even when they are innocent.

- Intellectual disability is often harder for people of color to prove, because many attended under-resourced schools and were never evaluated as children.

- Mental illness does not make people more likely to commit murder, but it does make them more likely to receive unfair trials and be sentenced to death.

- Mental illness has led some people to fire their attorneys and represent themselves at capital trials, even while in the grips of delusions.