‘I’m proud of my life’: A death row exoneree reflects on his long journey to freedom

By Helen Spielman

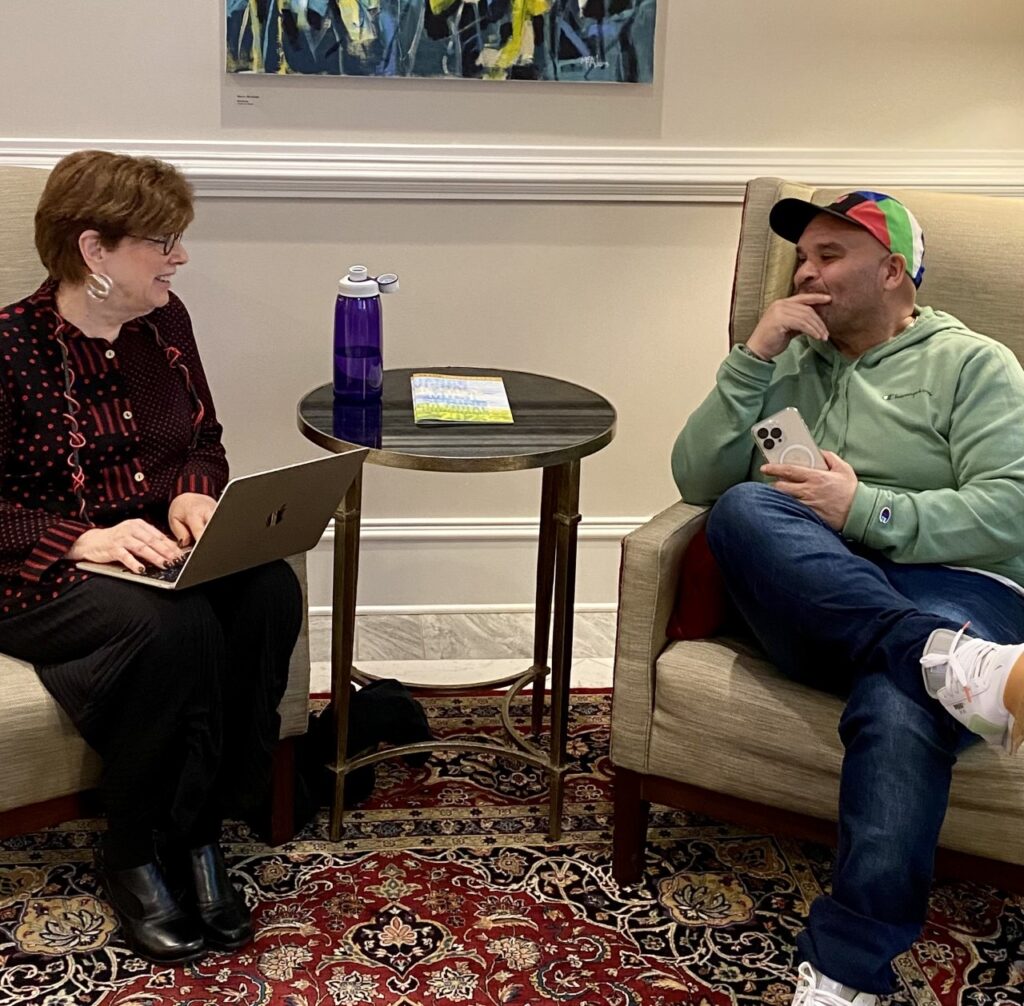

As I drive down the interstate to interview Alfred Rivera, one of the twelve men exonerated from North Carolina’s death row, my mind reviews ways to help Alfred feel comfortable to tell me about his life. We meet in the beautiful, quiet lobby of the Inn at Elon College, giving each other a warm hug, settling into soft chairs near a window. Alfred needs none of my carefully prepared speeches, launching without preamble into an enthusiastic description of his family.

“I’ve got three daughters aged 21, 22, 23, and a son aged 26. They all still live at home, working toward careers and doing well. My wife and I don’t want them making mistakes. We feel it’s good for them to have guidance and a structured environment until they fly away. At 25, I didn’t know who I was, psychologically. I thought I was mature, but, looking back, I realize how wrong I was.

“I just came from a special time with my wife, for Valentine’s Day, y’know.”

“Are you a decent husband?” I quipped.

“Oh, yeah, I got her flowers and chocolate and the whole thing,” he replied with a glint in his eyes.

Alfred, 52, is kind, soft-spoken, unpretentious. He’s wearing a green sweatshirt, white sneakers, and a baseball cap. I wonder how his earlier life could’ve gone so horribly wrong.

Alfred’s heritage is Puerto Rican. He grew up in the Crown Heights neighborhood of Brooklyn, NY, at the height of that area’s drug and crime era. His father, who owned a convenience store, was killed during a robbery when Alfred was four. His mother, left alone to raise five children, began drinking. When Alfred was 11, he found her on the kitchen floor as she was dying and stayed with her until her last breath.

My whole self becomes still as I try to imagine – impossibly, unimaginably – the experience of little Alfred.

“I feel a void when I remember my dad,” says Alfred when I ask how those losses feel now. “I was blessed to have him. I think of the lost opportunity, for myself, my siblings, my mom. His murder defined my childhood, and I consider my mother’s death to be a murder, too, perpetrated by the people who killed my father. After my mom died, we got split up to be raised by aunts and uncles.”

Before his parents’ deaths, Alfred was attracted to spirituality and loved to learn and read. But afterward, he turned to drugs and crime. I ask him about that first moment when he made a bad choice. Alfred sits up straight, begins gesturing, and becomes passionate.

“You have to understand, it wasn’t a moment. It was the poverty and pain and conditions of my environment. I grew up during the Brooklyn heroin epidemic among abandoned buildings, slums. It was a living hell. It had all been poured into me: seeing, hearing, suffering, and affecting a child in poverty. We had nothing in the apartment. By the time I was 15, I hit the streets to find my way out. I’m selling drugs with my buddies, but my situation was compounded through the loss of my parents. I wanted nice things, like a good pair of sneakers. You can see my immature mind. What did I think I would achieve? The reason there was so much crime is the people were pressed up against the wall. Am I going anywhere? Of course not!”

Alfred dropped out of school in tenth grade. By his early twenties, he had served two six-month prison terms for marijuana and cocaine possession. And then, at age 25, Alfred was sentenced to North Carolina’s death row, convicted of a murder he had not committed.

“What was that like for you?” I ask.

“Getting sentenced to death is the most horrible thing. I can’t express it.” Alfred breaks eye contact and stares into the distance.

I wait.

“Disbelief, alone, fear: all in one. Overwhelmed. The loneliness. On this little island and you’re done. I can’t win. My hands are totally tied. Death becomes magnified. I feel completely helpless. My family can’t save me. My attorneys can’t do anything. I didn’t commit this crime and I’m still done. The only ones who can help me are against me.”

I ask Alfred to clarify this last shattering statement.

“What I meant is that the system – our society — is fashioned in a way that many of those who are charged with assisting us Black and Brown people in America are the same ones who are targeting us to fail in all areas of our existence.”

I nod, absorbing this painful truth, and ask him to go on. Alfred was one of North Carolina’s luckier exonerees. Unlike Henry McCollum, who spent 30 years on death row, he won a new trial and was acquitted after two years. He was released in 1999, but leaving death row did not free him from his trauma.

“No one ever evaluated or helped me; no one ever explained anything. The state fails to ensure that exonerees like me are situated in a manner that would allow them to reacclimate and flourish in society despite their lives having been shattered by the ordeal. So, two years after I got off death row, when I was 29, I was caught with drugs and sent to federal prison for over 19 years. I’ve been out since July 3, 2019.”

Now, I’m astounded, because I’m listening to a man who speaks with the vocabulary of a learned scholar and who has great presence.

“How did you change? What happened?” I’m dying to know.

“I delved more deeply into spirituality in federal prison. I was brought up in Islam. Mom converted after dad was murdered, looking for comfort, and she gave us small pieces of that ideology. I learned Arabic as a child by going to the Mosque. I remember a guy from Yemen on the corner in Brooklyn. I recited the Fatia opening prayer for him. He was amazed by this little Puerto Rican kid. He said, ‘You come and recite more prayers, every day you get a soda and candy bar.’ I still know that store and that man’s sons. There came a time when religion became clear: I felt in my heart that The Most High does exist. I studied Buddhism, which did so much for me. It taught me about existing, and the breath taught me to come to terms with……everything. I studied the Egyptian deities. I learned how everything is related. But even now, my foundation is Islam, within which I feel cherished and through which I understand why I exist. I have a purpose: to help. My life was not destined to be easy, and all great things take sacrifice.

“I completed my GED within three weeks while waiting for the federal sentence. Over the years, I took over 50 adult continuing education courses, and I became an inmate instructor in history and Black history. I wanted to better myself. I read books, tons of books. Malcolm X wrote, ‘Prison is a playground for a fool and a university for a wise man.’ That inspired me. Do I sit here and deteriorate, or do I flourish and help someone else? That’s what made me who I am today.

“When I think about the people who perpetuate the system, I feel angry. We have people in powerful positions who are derelict in their duty to society. I feel a sense of rage toward them. It’s all over our country — this is what’s really going on.”

I swallow my shame and sorrow. Like so many white people, I lived most of my life with no knowledge of systemic racism. I ask Alfred how he lives with the weight of his experiences and how he gets through his days.

He tells me how he’s been working to start a shipping and delivery business. How he researches the history of oppression in America, to place himself in a lineage of those who have had to struggle for freedom in this country. He makes sure to express deep gratitude for the many people who have helped him over the years: friends, family, and attorneys Richard Ramsey, Doug Meis and Clarke Fischer, who worked tirelessly to free him from death row. And he talks about his current job as Lived Experience Coordinator with the NC Coalition for Alternatives to the Death Penalty: “Maybe we can influence the governor to find a different path than death row.”

As he does this work, he uses his own experiences to guide him. In the wake of his father’s murder, the death penalty did nothing for his family. He thinks about the state services that might have made a difference.

“You know, my family back then would’ve been helped by some financial support, assistance for my mother’s mental health, and guidance for her to raise us kids. We were victims with no support, and the prosecution of my father’s case was only one small part of the healing. That crime happened 50 years ago, and the same lack of support for crime victims is happening today. We can’t just feel sorry. We have to do something and take action to change this unjust and racist system.”

After three hours of conversation, Alfred and I decide it’s time to hit the road, he toward the west and I eastward. He easily could’ve gone on longer, and I’d have gladly been his student. We knew we’d see each other again at future Coalition meetings and events. As I drove home, I kept returning to something Alfred said that seemed to sum up how profoundly broken our criminal legal system is, as well as how the human spirit can flourish despite the inhumane way we treat so many of our fellow citizens.

“Do you know,” Alfred said, “in all these years, in and out of prison, I’ve never once been offered a session with a counselor? Never seen one. But I’m proud of my life, and of my journey of wisdom and understanding.”