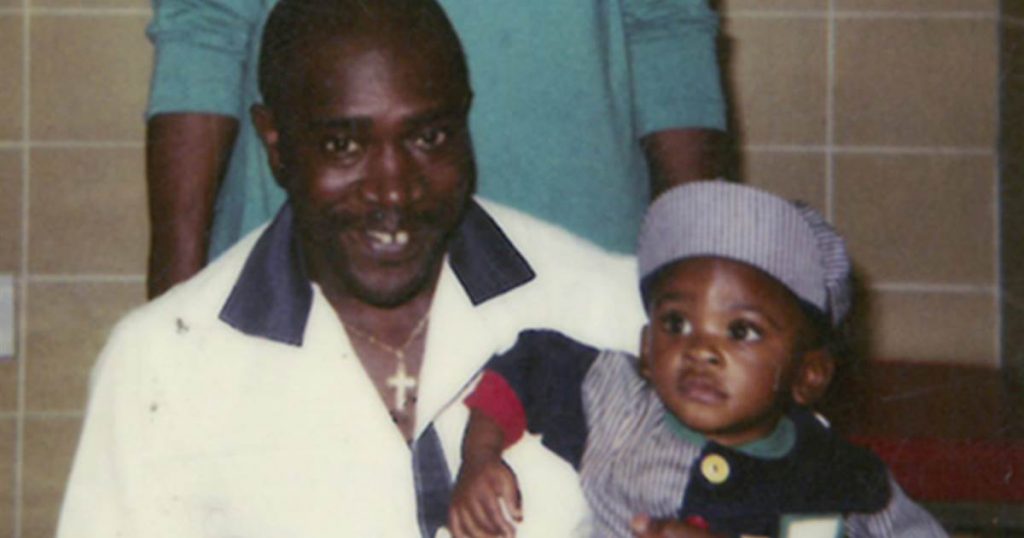

Last week, the Supreme Court halted the execution of Keith Tharpe in Georgia because of a juror’s admission that he voted for death because he believed Tharpe was a “n—-r.”

“After studying the Bible,” the juror said, “I have wondered if black people even have souls.” Prosecutors later made the ludicrous claim that, when the juror said “n—-r,” he didn’t mean it in a racist way.

This kind of racism in a life-or-death trial flies in the face of our country’s most basic beliefs about justice. It might be tempting to believe this case was just an anomaly. But Keith Tharpe is far from the only defendant to be sentenced to death by a deeply racist juror.

Just look at these North Carolina cases:

Kenneth Rouse was sent to N.C. death row 1992, the same year Tharpe received his sentence in Georgia. After the trial, one of Rouse’s jurors told defense investigators that “bigotry” played an important role in his decision. The juror also used the n-word and said that “black men rape white women so they can brag about it to their friends.” He said he believed that “blacks do not care about living as much as whites do.” Rouse remains on death row.

At Robert Bacon’s trial in 1987, jurors made racist jokes and held it against Bacon that he was dating a white woman. He eventually won clemency from the governor.

Like many death row inmates, Rouse and Bacon were sentenced by all-white juries. Often, prosecutors make explicitly racial appeals to white juries. Both of these men remain on death row:

During his trial in front of an all-white jury, Guy LeGrande was called a “n—-r” by three separate witnesses. The Stanly County prosecutor, known for wearing a noose-shaped lapel pin, invoked the image of evidence that would come together “twisted and bound into a rope.”

A prosecutor at Rayford Burke‘s trial referred to him as a “big black bull” during closing arguments in front of the all-white jury.

Diverse juries are key to driving racism out of capital sentencing. Studies show that they deliberate more thoroughly and make fewer mistakes. Juries with people of color are also less likely to be swayed by prosecutors who use racial stereotypes to push for death sentences.

Yet, the practice of excluding people of color from juries remains rampant in N.C. capital trials.

Prosecutors are more than twice as likely to strike qualified African Americans as they are to strike whites. More than 60 of N.C.’s 145 death row inmates were sentenced by juries with no more than one person of color. More than 25 of them had all-white juries.

The legislature repealed the Racial Justice Act, which was enacted to remedy jury discrimination, and the courts have refused to hear more than 100 claims of such discrimination brought by N.C. death row inmates.

Georgia is not an exception. In North Carolina and across the country, we are a long way from fulfilling our promise of color-blind justice, even in life-and-death trials.

Visit nccadp.org to learn

Visit nccadp.org to learn